Imagine being on a professional basketball team where you train every single day, but you don’t play with your teammates until the game starts. That’s basically how we work as actors in film and television (because so much of “finding” a character and preparing is done on your own). To help you be effective in this independent acting preparation, this article provides descriptions (with examples) of various traditional and new acting exercises you can do at home by yourself.

Traditional acting exercises include experimenting with different character backstories to enrich the emotions behind your line delivery and learning to adapt quickly by varying emotions with which you deliver or respond to lines. Some newer, faster-to-do exercises include mimicking and responding to actors on TV and performing quotes from IMDB.

To help you see what goes on in an actor’s mind when performing these exercises, below are descriptions, specific examples, and tips for how to perform these exercises. By looking at and understanding these examples, perhaps you may even develop your own exercises later.

Traditional Exercises

The ability to focus and work by yourself, and to imagine yourself in all kinds of situations, is a huge and underrated asset, and it is an actor’s fundamental skill. I’m talking about the kind of focus that makes you look at a line over and over and over and ask yourself, “What is it that I can bring to this line?” Even when it’s a simple line. Go deep even if you’re just starting out and playing the part of a shop clerk, with one or two lines like, “May I help you?” and, “That’ll be twelve-fifty.” Focus on the lines in utter privacy to discover and learn. This might seem like going overboard but remember that acting is a muscle. What you can do to one line, you can to a whole script; the more you do it the easier it becomes. The exercises below will help you build that acting muscle.

Backstories

As an actor, you have to be able to identify things that aren’t necessarily part of the performance but allow you to embrace the “character”. Here’s the first thing you can do when you are working alone: backstories. A backstory is just a made-up history for your character. Create several backstories and play a scene using those backstories.

Remember the two lines of the shop clerk we mentioned earlier: “May I help you?” and, “That’ll be twelve fifty.”

- What if you, as the shop clerk, had been running late for work and didn’t get a chance to have breakfast (and you typically always have breakfast)? How would that affect the delivery of those lines?

- Or suppose you had been having a really great day but, 5 minutes before this scene takes place, you had a really prissy customer who spent a lot of time letting out their frustration on you. How would that affect your delivery of those lines?

- Or suppose that this is your store and you’ve worked the last 20 years to make it successful and have a lot of pride in what you do. How would that affect the delivery of those lines?

As an actor, variety is key. Don’t just create one, but rather create several backstories. This is crucial because, as an actor, you have to be ready to change instantly depending on what your partner gives you. Acting without reacting is just . . . bad acting.

Therefore, when you are shooting the film or show, instead of choosing one of those backstories because you like the way you deliver lines with it, be ready to throw it all away and respond naturally based on what the other actor gives you. Which brings us to the second acting exercise.

Emotional Variety

Suppose that, one day of filming, the other actor is supposed to say, “I’ll take that bottle of gin.” There are many emotions with which that line can be said. While you’re rehearsing alone at home, you can consider the different possible emotions with which your scene partner’s line can be delivered, and experiment with different emotions when giving your response.

Remember the lines of the shop clerk we mentioned earlier. Imagine that the customer says, “I’ll take that bottle of gin,” and you reply, “That’ll be twelve fifty.”

- Suppose that “I’ll take that bottle of gin” line was delivered with aggression. How would that change your delivery?

- Or suppose that line was delivered with nervousness and fear. How would that change your delivery?

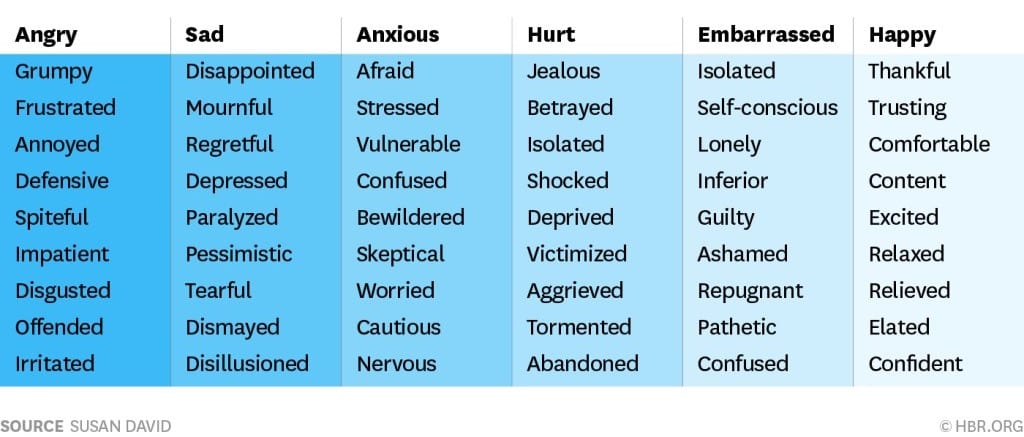

You can experiment with a variety of different deliveries and responses. One of my favourite things to do for this exercise is to use the table below. I imagine someone giving me their lines with each one of the emotions on the table and I ask myself: “How would I respond?” Or, “What would that make me think?” I would then do the same thing with my responses, trying a different emotion every time.

Again, this is not to find the “right” way but to have a variety of ways to perform. This exercise is to help you build a well-rounded emotional character and to also help you “throw things away”. In other words, if on the day of the actual performance your fellow actor gives you something that doesn’t justify the original delivery you planned, you are able to “throw away” what you had planned, and adapt, performing in a way that fits in with what your fellow actor gives you.

Let’s go a step further. Imagine yourself running through the same three lines:

“May I help you?”

“I’ll take that bottle of gin.”

“That’ll be twelve fifty.”

Now, attach a different emotion to each one of those lines, and it doesn’t matter if it does or doesn’t make sense. Below is an example.

- Practice delivering the lines below (with the indicated emotions) until you think you can deliver them convincingly, until you build a backstory that makes those emotions make sense.

“May I help you?” (elated)

“I’ll take that bottle of gin.” (annoyed)

“That’ll be twelve fifty.” (defeated)

- Then . . . throw it all away. Do something completely different.

“May I help you?” (regretful)

“I’ll take that bottle of gin.” (confused)

“That’ll be twelve fifty.” (thankful)

- Practice the above few times until you think you can deliver it convincingly and … you guessed it. Throw it all away and do something different.

At this point you might be thinking to yourself: “This is a lot of work for just a couple of lines.” And you are right, but this is the hard work that good acting requires. We only see the end product, the tip of the iceberg, the 2 weeks dedicated to mastering 10 lines. This is why acting is challenging: it’s not about memorizing lines – it’s about investigating endlessly. Talk to any actor who has performed in a play, and they will tell you that even after weeks of performing, at the end of the play’s run, they were still discovering new things in the lines.

There’s also another question here: What happens if you have a large part? What happens if you’re doing a whole play? Should we be doing this exercise for every single possible line? What if you have hundreds of lines? Isn’t that going to take forever? Let me answer this for you in a couple of different ways.

- Think back to the beginning of this article when we discuss the ability to focus and concentrate in privacy. Yes, acting is a lot of work for this very reason. Because it involves focus and mental effort.

- Let’s also remember that, if this acting ability is a muscle we are exercising, the more we exercise it the easier it gets. You do a lot of work as you are learning to become an actor to build the muscle. The more you do this exercise, the quicker you’ll be able to go through it. As you continue to work and build your muscle, you’ll need to do the exercise less and less because you’ll be able to just genuinely respond with very little background work. You’ll be able to quickly empathize and think of different emotional responses. Remember that the goal is creating that diversity so you can easily respond to what your other actor gives you.

Speaking personally, I know that I run through this exercise all the time even when I have larger parts, and it takes a while but I’m better for it. That being said, every actor has their own methodology, and you might never find an easy time of this exercise; but not to worry, there are other exercises you can also use. Perhaps the next exercise is more up your alley.

Pretending to Wake Up and Pick Up a Phone

When you watch interviews with famous acting directors or teachers, they always, sooner or later, bring up a child’s ability to just pretend and be in the moment. And it’s true: your ability to pretend like a little kid can really help you overcome that self-consciousness and self-awareness and just be something or someone else.

One pretending exercise you can do is waking up. This is an exercise that was created by Uta Hagen, a very famous acting teacher, and it’s a great exercise to help you create a reality and lose yourself in that reality.

In this exercise, pretend you’re waking up because the phone is ringing.

- The first step here is to really delve into waking up … because waking up is not opening your eyes and getting out of bed. In fact, waking up is affected by a combination of several hours or days of events, isn’t it?

- For example, if you had a rough night or a busy night or a very normal night, each one of those will affect how you wake up.

Therefore, the first step is just practicing that waking up and some of the best advice I can give you for this exercise is to draw it out. Don’t open your eyes and reach for the phone. Wake up over the course of 1 to 5 minutes.

- Play the role of someone who wakes up easily and play the role of someone who doesn’t wake up easily.

- From there, we move onto the second part of the exercise, and that is answering the phone. Here you answer the phone with different options:

- The first option is it is someone you are really attracted to whom you just met.

- The second option is you pick up the phone, and it’s a wrong number.

For both these options:

- You imagine not only how you wake up, but the conversation you have, and how that affects how awake you are.

- You imagine a quick conversation and a long one. And you actually have those conversations, pretending you’re hearing things and responding with what you think is a natural reaction to what you’re hearing.

- Ask yourself what would happen after you hung up. Pretend to do that.

Here’s an example of what might go through my mind as I perform this exercise.

I wake up to the phone ringing, but I didn’t get a lot of sleep the night before (I had ended up watching a TV show and so I went to bed only 4 hours earlier). I let the phone ring several times hoping that it would stop and that the person would hang up quickly. But it doesn’t so, after 10 or 11 rings, I finally go grab the phone, pick it up without looking, and, a little bit grumpily, ask who it is. And it’s the girl I met a few nights earlier who I was really into. I had given her my number, and she’s actually calling me. All of a sudden, several things go through my mind:

Why did I answer the phone that way?

Oh my God, I can’t believe she’s calling me

What was your name again?

F*** what a terrible time to call

Okay, wake up, wake up, wake up

Be charming

Don’t be too needy

Play it cool

All of these thoughts are going through my head simultaneously even though I’m home alone speaking to my cell phone.

Then I make up a whole conversation. I won’t go through all the back-and-forth specifics here, because every time I do it it’s different, but I literally have 20 or 30 lines back and forth. Pleasantries, alluding to getting together again, actually making plans, and then saying goodbye.

Then, after all that is done, the scene isn’t over. How does that affect the way I hang up? The way I lie back down? Do I lie in bed and just be in those amazing feelings of happiness? Do I get up excitedly and start my day because of all the great joy?

I would pretend to be in that scene for as long as I want, because I’ll be home and I’ll be alone, and this is the actor’s discipline.

New Exercises for Faster Practices

Everything we discussed so far comes from the realm of traditional acting exercises and techniques. Those exercises you would first be introduced to in an acting class, and they are great but, as you can see, sometimes they’re quite involved. Therefore, I want to give you a few ways to micro practice. I want to give you a few ways that you can exercise your acting muscle for a few seconds to a few minutes with very little commitment.

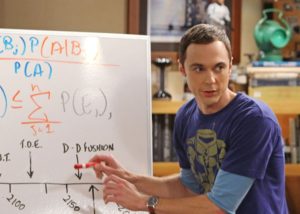

- Mimic or react to whatever you’re watching. The other night I was watching Game of Thrones and, essentially, when I saw a good conversation, I would listen to the talking and try to react sometimes. I would try and find my own reactions and, sometimes, I would mimic the reactions of the actors I saw on screen.

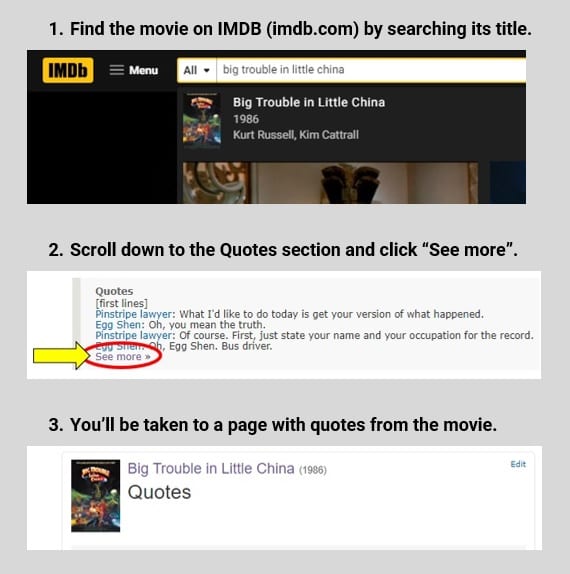

- Memorize and perform lines out loud. Sometimes as a small quick exercise, I like to go on IMDB, find random films, and check out the Quotes section. Not every TV show and movie has the quotes section, but quite a few do.

For example, I just did a search on IMDB for Big Trouble in Little China (an amazing movie from the 80s). I then scrolled down until I found Quotes and clicked “see more”. That takes you to the following link: Https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0090728/quotes/?Tab=qt&ref_=tt_trv_qu

From here you can just pick a few quotes that you can say to yourself throughout the course of the day just for fun.

You can pick movies that you like, but it’s usually better if you pick movies you don’t know, because then you don’t fall into the trap of performing it the way the actor from the movie did it. I take random lines, and I try to perform them over the course of an evening or days, depending on how long it took me to memorize it and/or how much I like it.

In general, personally, I like to find things that I can quickly absorb and then focus on performance, which is why I like practicing with short clips from IMDB and things that I’m already watching. These are things I can do quickly, and it’s almost like having cue cards instead of reading through a chapter when you’re studying. And, just like when you’re studying, it’s a great example of studying smart, not harder.